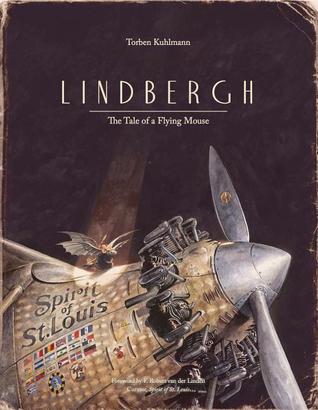

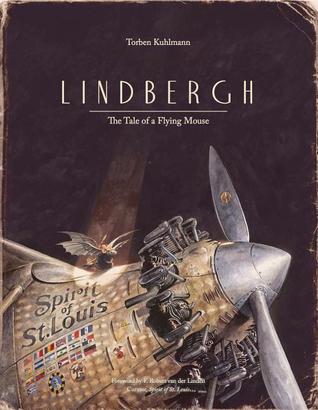

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world, with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links, portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action, again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studied the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Mr. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Mr. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Mr. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Mr. Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star. Highly recommended for ages 6 to 10.

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books.

See also …

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

– See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

– See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

– See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

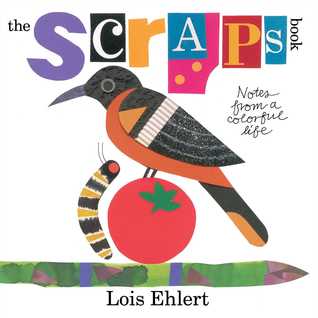

a Colorful Life

a Colorful Life

contemporary audience.

contemporary audience.

e.

e.