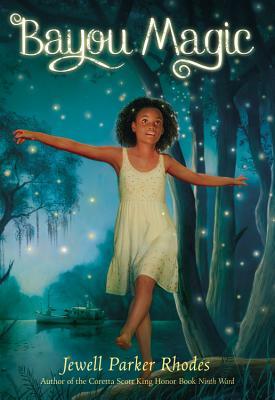

Maddy’s big sisters have warned her about going to Grandmère’s home deep in the Louisiana bayou. It’s boring, they say; there’s no TV, no mall, no microwave, and no indoor plumbing. Not only that, Grandmère’s a witch. Ten-year-old Maddy has a mind of her own, though, and anticipates adventures far from the glass and concrete world of New Orleans.

The magic begins on the car ride to the bayou. When a firefly perches on the rim of the car door, Maddy’s imagination is fired; surely it’s some kind of sign.

Grandmère doesn’t look like much of a sage. She’s tiny, “bird-boned,” with “bright-white curly hair, luminous like the moon.” Maddy and her grandmother settle into a cozy routine of humming together, collecting eggs from the hen, doing dishes, and sitting on the porch. As the days pass, Grandmère tells Maddy stories about her ancestors and teaches her important principles such as … respect yourself … pay attention … and leave space for imagination. Under Grandmère’s guidance, she will, over the course of the summer, discover her own power, her place in a long line of Lavaliers, and an enchanted land replete with helpful fireflies and mermaids.

Maddy gets to know the neighbors and makes herself at home in Bayou Bon Temps. “Folks, all colors, live in the bayou,” she muses. “Some are red-haired, some blond or brunette. A stew. They all feel like kin to me. Like a family I didn’t know I had.”

Perhaps best of all, she meets a wiry, energetic boy called Bear, and the two form a strong bond as they run around, get dirty, and explore the bayou together. Her adventure, or at least her imagination, takes off the day she sees a mermaid rise from the dark waters.

At first, Maddy reveals her secret to no one but Grandmère, who believes the girl has encountered the legendary Mami Wata, who followed imprisoned Africans forced to cross to North America in the dank holds of slave ships. Later, as an environmental disaster endangers the Bayou Bon Temps, Maddy calls upon her own powers, as well as help from fireflies and mermaids, to rescue the community she cherishes.

Middle-school girls with a fanciful flair will snap up this novel imbued with magical mystery and a young heroine’s hopeful imagination.

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books.

Don’t miss Jewell Parker Rhodes’s thoughtful comments on diversity in children’s literature.

And see my previous post on Sugar, winner of the Jane Adams Peace Association book award, and check out the author’s Coretta Scott King honor book, Ninth Ward.

e.

e.